|

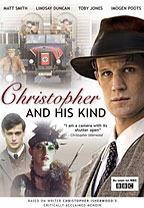

Christopher and his Kind

BFI Entertainment,

2011

Director:

Geoffrey Sax

Screenplay:

Kevin Elyot

Based on the memoir by Christopher Isherwood

Starring;

Matt Smith,

Imogen Poots,

Toby Jones,

Pip Carter,

Lindsay Duncan,

Douglas Booth,

Alexander Dreymon,

Perry Millward

Unrated,

90 minutes |

Goodbye to Berlin

by

Michael D. Klemm

Posted online September, 2013

Once upon a time, all queer historical figures were routinely “de-gayed” in the movies. The 1946 bio-pic Night and Day starred Cary Grant as Cole Porter and, not only was he straight, but he was also a war hero. Don’t even talk to me about Charlton Heston as Michelangelo in The Agony and the Ecstasy. This is happily not the case in the recent BBC film of Christopher Isherwood’s 1976 memoir, Christopher and his Kind. The film has barely begun when the elderly Isherwood, typing away at his manuscript, confesses that he went to Berlin in 1931 “because of the boys.” |

Christopher and his Kind (2011) is a loose, but very dramatic, adaptation of Isherwood’s book. It features an enigmatic and effective performance from Matt Smith (best known as the eleventh doctor on the BBC series Dr. Who) as the celebrated gay author. Isherwood’s friend, fellow gay poet W.H. Auden, wrote to him about the nightlife in Berlin and Christopher had to see for himself. Rejecting his role in polite British society, he wished to get down and dirty with foreign, working class youths. Before he leaves England, his disapproving mother tells him to “remember that the Germans killed your father.” Christopher doesn’t care, he just wants to get laid. Christopher and his Kind (2011) is a loose, but very dramatic, adaptation of Isherwood’s book. It features an enigmatic and effective performance from Matt Smith (best known as the eleventh doctor on the BBC series Dr. Who) as the celebrated gay author. Isherwood’s friend, fellow gay poet W.H. Auden, wrote to him about the nightlife in Berlin and Christopher had to see for himself. Rejecting his role in polite British society, he wished to get down and dirty with foreign, working class youths. Before he leaves England, his disapproving mother tells him to “remember that the Germans killed your father.” Christopher doesn’t care, he just wants to get laid.

|

|

|

A quick history lesson. Isherwood is best known as the author of Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Goodbye To Berlin (1939) – often collected as The Berlin Stories - which became the basis of the Broadway play, I Am A Camera and then the musical, Cabaret. (He also wrote A Single Man.) The stories were inspired by the author’s experiences in Berlin and populated by the people he met during his stay. Sally Bowles is based on his friend, cabaret singer Jean Ross. Because the books were written in the 1930s, the” gay stuff” had to be purged (he wrote his 1976 memoir to rectify those omissions). During the 1920s, Berlin was a period of unprecedented sexual freedom and “divine decadence.” This included a thriving gay scene. And then, as anyone who has seen Cabaret knows, the Nazis showed up and the party was over. |

But, when Isherwood first arrives in Berlin, life is a cabaret, old chum. Auden takes him to an underground club, The Cosy Corner, where a delighted Isherwood finds a cornucopia of available young men. Auden explains that most of them are “hetters” – unemployed straight boys more than willing to indulge a little gay for pay to make a living. Isherwood takes up with a beautiful blonde youth named Casper. The sex they enjoy is robust and athletic – and perhaps the loudest ever in the history of cinema (which is all the more comic because Isherwood is living in a boarding house). He becomes disillusioned when he realizes that all the young lad wants is money. But, when Isherwood first arrives in Berlin, life is a cabaret, old chum. Auden takes him to an underground club, The Cosy Corner, where a delighted Isherwood finds a cornucopia of available young men. Auden explains that most of them are “hetters” – unemployed straight boys more than willing to indulge a little gay for pay to make a living. Isherwood takes up with a beautiful blonde youth named Casper. The sex they enjoy is robust and athletic – and perhaps the loudest ever in the history of cinema (which is all the more comic because Isherwood is living in a boarding house). He becomes disillusioned when he realizes that all the young lad wants is money.

|

On the first page of Goodbye To Berlin, Isherwood famously wrote the words, “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” His screen incarnation coasts through Berlin, making friends and finding fodder for this stories, and is seemingly blind to the growing political chaos. All that slowly changes when he meets Heinz, a young street sweeper who becomes the first great love of his life. Now he has someone he needs to protect as the climate changes in Berlin. Their romance is idyllic but he knows now that it is ultimately doomed. Throw in a book burning, and the destruction of his Jewish friend’s department store, and he can no longer ignore the rise of Adolf Hitler (whom he mocked in the book and, at one point, wrote that “‘Charlie Chaplin’ has ceased to be funny”). Isherwood and Heinz left Berlin in 1933 to unsuccessfully search for a country where they could settle down and, eventually, Heinz was arrested and sent back to Germany. On the first page of Goodbye To Berlin, Isherwood famously wrote the words, “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” His screen incarnation coasts through Berlin, making friends and finding fodder for this stories, and is seemingly blind to the growing political chaos. All that slowly changes when he meets Heinz, a young street sweeper who becomes the first great love of his life. Now he has someone he needs to protect as the climate changes in Berlin. Their romance is idyllic but he knows now that it is ultimately doomed. Throw in a book burning, and the destruction of his Jewish friend’s department store, and he can no longer ignore the rise of Adolf Hitler (whom he mocked in the book and, at one point, wrote that “‘Charlie Chaplin’ has ceased to be funny”). Isherwood and Heinz left Berlin in 1933 to unsuccessfully search for a country where they could settle down and, eventually, Heinz was arrested and sent back to Germany.

|

But, before everything goes to hell, the viewer gets to have fun. Fans of the stage and screen versions of Cabaret will finally get to see Clifford Bradshaw / Brian Roberts explore his real sex life. Despite outward appearances of conformity and rectitude, he wanted to be a sexual outlaw. He shed all his inhibitions in Berlin and the film is quite explicit in this respect (the BBC did specify though that their new Doctor Who couldn’t show his willy). Look for lots of beefcake too; though there is a shot of the blonde and muscular Casper in the woods that seems a little too Triumph of the Will for comfort. Perhaps that was the point because he is later seen as a brownshirt. The Nazis appear slowly, almost like Universal horror film monsters. In a scene that is both uncomfortable and comic, Isherwood turns to check out the man that is standing at the next urinal and then tries to look nonchalant when he sees the brown uniform and the swastika. But, before everything goes to hell, the viewer gets to have fun. Fans of the stage and screen versions of Cabaret will finally get to see Clifford Bradshaw / Brian Roberts explore his real sex life. Despite outward appearances of conformity and rectitude, he wanted to be a sexual outlaw. He shed all his inhibitions in Berlin and the film is quite explicit in this respect (the BBC did specify though that their new Doctor Who couldn’t show his willy). Look for lots of beefcake too; though there is a shot of the blonde and muscular Casper in the woods that seems a little too Triumph of the Will for comfort. Perhaps that was the point because he is later seen as a brownshirt. The Nazis appear slowly, almost like Universal horror film monsters. In a scene that is both uncomfortable and comic, Isherwood turns to check out the man that is standing at the next urinal and then tries to look nonchalant when he sees the brown uniform and the swastika.

|

|

Matt Smith leads a terrific cast of delicious eccentrics. Toby Jones, known for his killer turns as Truman Capote and Alfred Hitchcock, is a hoot as the flamboyant smuggler, Gerald Hamilton. He is an over-the-top queen with an obvious wig who likes to be whipped. Imogen Poots is the “Sally Bowles” that we love but also shows a more serious side. Douglas Booth is more than just a pretty face as Heinz, but he does fulfill the requisite amounts of innocence and beauty. Pip Carter, as Auden, gets to be pithy while yearning for Christopher’s love. Lindsay Duncan is delightfully cold and overbearing as Isherwood’s mother. She blames all of Christopher’s troubles on the naughty Auden. |

Christopher and his Kind is a handsome production; somewhere between Masterpiece Theatre and Merchant-Ivory. A few liberties are taken, and much is left out, but it would require a mini-series to do the entire book. For good or ill, many characters were also combined. To be honest, the memoir’s last third often reads like travelogue as Isherwood flees with Heinz throughout Europe and, by eliminating this, the film maintains a greater dramatic focus. The relationship between Christopher and Heinz is actually more romantic too. Director Geoffrey Sax and his screenwriter, Kevin Elyot, might not please everyone with their adaptation but they did craft a tightly constructed film that is gripping and far from boring. Christopher and his Kind is a handsome production; somewhere between Masterpiece Theatre and Merchant-Ivory. A few liberties are taken, and much is left out, but it would require a mini-series to do the entire book. For good or ill, many characters were also combined. To be honest, the memoir’s last third often reads like travelogue as Isherwood flees with Heinz throughout Europe and, by eliminating this, the film maintains a greater dramatic focus. The relationship between Christopher and Heinz is actually more romantic too. Director Geoffrey Sax and his screenwriter, Kevin Elyot, might not please everyone with their adaptation but they did craft a tightly constructed film that is gripping and far from boring.

|

I liked most of this film a lot, but I confess that I do grieve for some of the book’s missing episodes. For example, Isherwood often visited Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science and this could have been the source of some sublime comedy. The book also described a screening of the 1919 silent film, Different From The Others (history’s first positive queer film - produced by Hirschfeld), being broken up by the Nazis. We also miss his friendships with a few more queer writers, namely E.M. Forster and Klaus Mann. I liked most of this film a lot, but I confess that I do grieve for some of the book’s missing episodes. For example, Isherwood often visited Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science and this could have been the source of some sublime comedy. The book also described a screening of the 1919 silent film, Different From The Others (history’s first positive queer film - produced by Hirschfeld), being broken up by the Nazis. We also miss his friendships with a few more queer writers, namely E.M. Forster and Klaus Mann.

|

|

But a film, unlike a book, can’t have too many notes and a sprawling book needs to be pruned for the screen. Elyot’s script pares the book down to its emotional core, and I liked how the resulting framework pays homage to both Isherwood’s own Berlin Stories and Bob Fosse’s 1972 film of Cabaret. The film begins with Isherwood and Gerald Hamilton meeting on the train to Berlin in much the same way that their fictional counterparts met on the first page of Mr. Norris Changes Trains. When Jean Ross plays the chanteuse on the nightclub stage, images of Fosse’s musical are evoked but - unlike the more widely known powerhouse Sally Bowles personified by Liza Minnelli - she is closer to Isherwood’s original character and so her singing is dreadful. The ending, I admit, is a little choppy, but it fills in all the details that the viewer needs to know regarding what happened to everyone after the war. |

Isherwood aficionados might be hungry for more, but should also recognize the amount of care taken with many of the small touches. Wikipedia reports that the dolphin clock, seen in the film, is the actual clock from Isherwood’s room in Berlin. Isherwood’s longtime partner, Don Bachardy, loaned it to the filmmakers. I also liked the photo of Isherwood and Bachardy that was next to the elderly writer’s typewriter in the film’s coda. Christopher and his Kind might not please everyone, but it is entertaining and informative and not, by any means, a dry history lesson. Isherwood aficionados might be hungry for more, but should also recognize the amount of care taken with many of the small touches. Wikipedia reports that the dolphin clock, seen in the film, is the actual clock from Isherwood’s room in Berlin. Isherwood’s longtime partner, Don Bachardy, loaned it to the filmmakers. I also liked the photo of Isherwood and Bachardy that was next to the elderly writer’s typewriter in the film’s coda. Christopher and his Kind might not please everyone, but it is entertaining and informative and not, by any means, a dry history lesson.

If you’re interested in more about Isherwood’s life, check out Chris and Don: A Love Story, the excellent documentary about his thirty-four year relationship with artist Don Bachardy.

More on Christopher Isherwood:

Chris and Don: A Love Story

A Single Man |